The history of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) is a testament to the geopolitical dynamics and technological advancements that shaped the Cold War era and beyond. Emerging as a pivotal component of strategic military arsenals, ICBMs played a central role in the tense standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union during the mid-20th century.

The origins of ICBMs can be traced back to the aftermath of World War II, when the Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union began to intensify. As both superpowers sought to assert their dominance and expand their spheres of influence, the development of long-range ballistic missiles became a strategic imperative. The advent of nuclear weapons added a new dimension to military strategy, prompting nations to explore ways to deliver these potent payloads across vast distances.

The first practical strides in ICBM development occurred in the late 1950s, with the United States and the Soviet Union leading the way. The U.S. Army’s Redstone and Jupiter missiles marked early American efforts, while the Soviet Union achieved a milestone with the R-7 Semyorka, the world’s first ICBM. The successful launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite by the Soviet Union in 1957, further escalated the Cold War space race. It underscored the potential of ICBMs as instruments of global influence.

Throughout the Cold War, both superpowers engaged in a technological arms race, continually refining and expanding their ICBM capabilities. The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 brought the world to the brink of nuclear conflict, highlighting the geopolitical implications of ICBMs and their role in shaping international relations.

As the Cold War eventually thawed, ICBMs continued to evolve, and additional nations joined the nuclear club, further complicating global security dynamics. Today, the legacy of ICBMs endures as a symbol of the complex interplay between military strategy, technological innovation, and international diplomacy in an era defined by the specter of nuclear conflict.

Table of Contents

Which ICBM has the longest range?

The DF-41, or Dongfeng-41, is considered one of the ICBMs with the longest range. The DF-41 is a Chinese intercontinental ballistic missile developed by the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). It is part of China’s nuclear deterrent strategy and is believed to have entered service in the early 2020s.

The DF-41 has an estimated range of over 12,000 kilometers (7,456 miles), making it one of the longest-range ICBMs in the world. This extended range allows China to target locations across the globe, enhancing its strategic capabilities. The missile is also reported to be equipped with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), further increasing its effectiveness.

The development and deployment of the DF-41 represent China’s efforts to modernize and strengthen its nuclear forces. The missile’s extended range provides China with the ability to maintain a credible second-strike capability, allowing for a more robust and flexible nuclear deterrent.

It’s important to note that the field of strategic missile capabilities is dynamic. Additionally, specific details about certain missile systems, including their exact range and capabilities, are often closely guarded by the respective countries for security reasons. Therefore, information available to the public may be limited, and estimates are based on analyses by experts in the field.

When was the first US ICBM?

The first operational Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) developed by the United States was the SM-65 Atlas. Development of the Atlas began in the late 1950s, spurred by the Cold War competition with the Soviet Union. The Atlas program aimed to create a missile capable of carrying nuclear warheads over intercontinental distances.

The Atlas D, the first operational version of the missile, became the United States’ first true ICBM and achieved its first successful test flight on December 17, 1957. This event marked a significant milestone in the arms race between the superpowers during the Cold War.

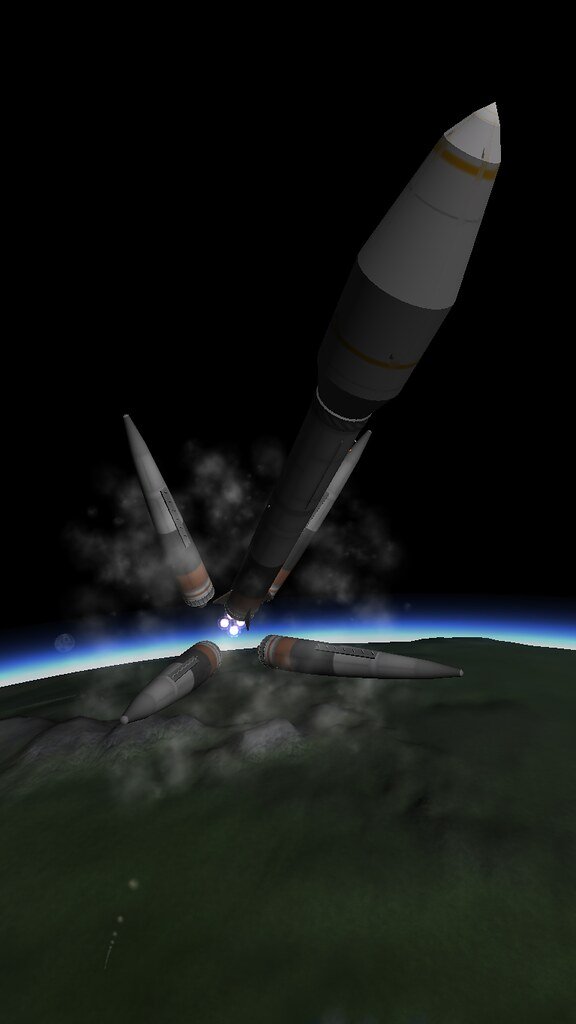

The Atlas D was a liquid-fueled rocket, standing approximately 75 feet tall. It had a range of over 9,000 kilometers (5,600 miles) and could deliver a nuclear payload to targets in the Soviet Union. The missile had a distinctive “balloon” or “stage-and-a-half” design, featuring a large central fuel tank and two smaller boosters attached to the sides.

The Atlas played a crucial role in the early years of the U.S. ICBM program and also served as the launch vehicle for the Mercury space program, carrying the first American astronauts into space. Over time, the Atlas missile underwent various upgrades and modifications, contributing to the development of subsequent ICBM systems.

The success of the Atlas program demonstrated the United States capability to deploy long-range missiles with global reach, providing a key component of its strategic nuclear deterrent. The Atlas series continued to evolve, with later versions contributing to advancements in multiple-warhead deployment (MIRV) technologies. The Atlas ICBMs remained in service for several years before being phased out as newer missile systems were developed.

ICBM History

An Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) is a long-range missile designed for nuclear weapons delivery, typically with a range of more than 5,500 kilometers (3,418 miles). The development and history of ICBMs are closely tied to the Cold War, a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union. Here’s a brief overview of the history of ICBMs:

World War II Roots (1940s)

The concept of long-range missiles capable of delivering potent warheads, driven by the evolving nature of military technology, emerged during World War II. One of the pivotal developments in this era was the creation of the German V-2 rocket, a groundbreaking achievement attributed to Wernher von Braun. The V-2, or A-4, represented the world’s first operational long-range guided ballistic missile.

Developed by Nazi Germany in the latter stages of World War II, the V-2 rocket was powered by a liquid-fueled engine and featured advanced guidance systems. Standing as a technological marvel of its time, the V-2 was capable of reaching altitudes of over 180 kilometers (112 miles) and achieving speeds exceeding 5,000 kilometers per hour (3,100 miles per hour).

Despite its technological significance, the V-2’s military impact was limited due to the late stage of its deployment in the war. Nevertheless, Wernher von Braun’s work on the V-2 laid the foundation for subsequent advancements in rocketry and space exploration, particularly in the context of the Cold War space race between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Post-World War II (1945-1950s)

After World War II, the race to acquire German rocket technology and the expertise of scientists like Wernher von Braun became pivotal in the early stages of the Cold War. The United States and the Soviet Union recognized the potential of German advancements, particularly the V-2 rocket, which had demonstrated unprecedented capabilities in terms of range and altitude during the war. As the geopolitical landscape shifted into the Cold War era, both superpowers sought to harness this cutting-edge technology for military purposes.

The escalating tensions of the Cold War fueled intense competition between the United States and the Soviet Union. The fear of nuclear conflict and the need for a strategic advantage prompted the rapid development of ballistic missile capabilities. The realization that these missiles could deliver devastating payloads over vast distances led to a strategic shift in military thinking. Ballistic missiles emerged as critical components of national defense strategies, setting the stage for the subsequent development of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) as potent symbols of deterrence during the Cold War.

R-7 Semyorka (1957)

The Soviet Union’s launch of the R-7 Semyorka on October 4, 1957, heralded a transformative moment in human history by initiating the space age. This historic event marked the world’s first successful launch of an artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, into Earth’s orbit. The R-7, designed by Chief Designer Sergei Korolev, played a pivotal role in this achievement, showcasing the Soviet Union’s prowess in rocket technology.

The R-7’s innovative design not only enabled the launch of Sputnik but also laid the foundation for its dual-use capability as an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM). Its adaptability for space exploration and military applications made it a groundbreaking technological achievement. The R-7’s success spurred subsequent developments in Soviet missile design, contributing to the arms race between the superpowers during the Cold War.

The launch of Sputnik 1 had profound geopolitical implications, intensifying the space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The event triggered increased investments in science, technology, and education as nations recognized the strategic and symbolic importance of space exploration. The R-7’s dual role as both a space launch vehicle and an ICBM exemplified the interconnectedness of space exploration and military capabilities during this pivotal period.

Atlas and Titan (1959-1960)

The United States developed the Atlas and Titan series of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) as a response to the escalating Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union. Among these, the Atlas D stood out as a pioneering achievement, becoming the nation’s first operational ICBM in 1959. The Atlas D’s successful deployment marked a significant milestone in the U.S. military’s quest for a strategic nuclear deterrent.

The Atlas and Titan missiles were vital components of the U.S. nuclear deterrent strategy during the Cold War. With their intercontinental range, these missiles could reach targets deep within the Soviet Union, showcasing America’s capacity for long-range precision strike capabilities. Beyond their primary role as strategic deterrents, these ICBMs also played a dual role in space exploration. The Atlas rocket, for instance, served as the launch vehicle for the Mercury spacecraft, enabling the United States to propel its first astronauts into space. The development and deployment of these missile systems underscored the geopolitical and technological competition that defined the Cold War era, shaping the strategic landscape of global power dynamics.

Cuban Missile Crisis (1962)

The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 marked one of the most challenging moments in the Cold War, highlighting the strategic significance of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs). The crisis erupted when the United States discovered evidence of Soviet ballistic missiles being deployed in Cuba, capable of reaching U.S. cities within minutes. This revelation triggered a tense, thirteen-day standoff between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

President John F. Kennedy, in response to the perceived threat, implemented a naval blockade around Cuba, demanding the removal of the missiles. The world watched anxiously as the two superpowers engaged in intense diplomatic negotiations. The crisis reached its peak when the U.S. and the Soviet Union stood on the brink of nuclear conflict.

The Cuban Missile Crisis underscored the critical role of ICBMs in shaping global geopolitics. The proximity of Soviet missiles in Cuba heightened the risk of a rapid and devastating nuclear exchange. The resolution of the crisis, marked by the removal of missiles from Cuba and a secret agreement to dismantle U.S. missiles in Turkey, emphasized the delicate balance maintained through strategic arms and the severe consequences that could arise from the deployment of ICBMs in sensitive locations.

Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs) (1970s)

Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs) represented a significant advancement in the capabilities of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) during the Cold War. Developed by both the United States and the Soviet Union, MIRV technology allowed a single missile to carry multiple warheads, each with its guidance system and the capacity to target different locations independently.

MIRVs enhanced the strategic and tactical flexibility of ICBMs, effectively multiplying the destructive potential of a single missile launch. Instead of delivering a single warhead to a designated target, MIRV-equipped missiles could disperse multiple warheads across a wide area, challenging enemy defenses and increasing the likelihood of target destruction. This capability added complexity to missile defense systems, making it more challenging for adversaries to intercept and neutralize incoming warheads.

The deployment of MIRVs also had profound implications for arms control negotiations, as it complicated efforts to limit the number of nuclear warheads held by each superpower. The development and proliferation of MIRV technology further underscored the intense technological competition and strategic considerations that defined the Cold War era, shaping the dynamics of nuclear deterrence and global security.

Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START) (1980s-1990s)

The U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a series of arms control negotiations during the late Cold War period, resulting in the signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START I and START II). These landmark agreements aimed to address the growing concerns of a nuclear arms race and sought substantial reductions in the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons.

START I, signed in July 1991, marked a historic step in arms control by committing both nations to significant cuts in their arsenals. The treaty mandated the reduction of deployed strategic nuclear warheads to 6,000, limiting the number of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers.

Building on the foundation of START I, START II, signed in 1993, sought even deeper reductions. It proposed to reduce deployed strategic nuclear warheads to 3,000-3,500 by eliminating multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) on ICBMs. Although START II still needs to be fully ratified or implemented due to various geopolitical challenges, these agreements set the stage for future arms control efforts and contributed to the overall reduction of nuclear weapons during a critical period of global security transformation.

Post-Cold War Era (1990s-2000s)

Following the end of the Cold War, a significant shift occurred in the strategic landscape, leading to substantial reductions in the number of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) deployed by both the United States and Russia. The conclusion of the Cold War prompted a reassessment of nuclear postures and a move towards arms control agreements. Key treaties, such as the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START I and START II), were negotiated, aiming to limit the number of strategic nuclear weapons.

Simultaneously, other nations, particularly China, sought to enhance their military capabilities, including the development of ICBMs. China emerged as a notable player in the realm of intercontinental ballistic missile technology, marking a shift in the global balance of power. The Chinese government, recognizing the strategic importance of possessing a credible nuclear deterrent, invested in the research and development of ICBMs, further diversifying the geopolitical landscape and impacting global security dynamics. This dynamic evolution underscored the complex interplay of disarmament efforts and the pursuit of advanced missile capabilities among emerging powers in the post-Cold War era.

Modern Era (2000s-Present)

In the contemporary era, Russia and the United States persist in maintaining and modernizing their Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) arsenals, albeit with a notable reduction in the overall number of deployed missiles compared to the peak of the Cold War. Arms control agreements, such as the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START), have played a role in limiting the number of strategic nuclear weapons held by these two major powers.

Meanwhile, the proliferation of ICBM capabilities has extended beyond the Cold War competitors. China, for instance, has actively developed and expanded its ICBM capabilities, enhancing its strategic posture on the global stage. North Korea has also pursued the development of ICBMs, raising concerns within the international community regarding the potential threat these capabilities pose. Other nations may be exploring or advancing their own ICBM programs, contributing to a complex and evolving landscape of strategic missile capabilities worldwide. This situation underscores the ongoing significance of ICBMs in shaping global security dynamics and emphasizes the importance of international efforts to prevent the proliferation of these potent weapons.

ICBMs, or Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, persist as pivotal elements in the strategic arsenals of nuclear-armed nations, embodying the essence of deterrence strategies that define nuclear weapons policies worldwide. Serving as the long-reaching arm of a nation’s nuclear capabilities, ICBMs are designed to deliver devastating payloads across continents, thereby dissuading potential adversaries from initiating aggression.

The history of ICBMs mirrors the dynamic interplay of geopolitical and technological forces throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Born from the intense Cold War rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union, these missiles symbolize the technical prowess and strategic understanding of their respective developers. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 underscored their geopolitical significance, almost triggering a nuclear conflict. Over the years, arms control treaties aimed at limiting the number of deployed ICBMs have shaped the global nuclear landscape.

In the modern era, nations such as Russia, the United States, and others continually refine and modernize their ICBM arsenals, adapting to evolving geopolitical realities. The enduring presence of ICBMs underscores their enduring role in shaping global security dynamics and maintaining a delicate balance of power in the nuclear age.