The GNU Project is a cornerstone of the free software movement and a fundamental pillar in the history of Linux. Launched in 1983 by programmer Richard Stallman, GNU set out to create a complete, Unix-like operating system that would be entirely free software – meaning users have the freedom to run, study, modify, and share the software for any purpose. This ambitious project not only produced many of the core components that modern computing relies on, but also ignited a global philosophical movement advocating for software freedom. In fact, GNU’s principles and licenses (like the GNU General Public License) introduced the concept of copyleft, ensuring software remains free and open for all users.

Many people today run GNU every day without realizing it, because GNU is at the heart of what is popularly called the Linux operating system. This comprehensive guide will explore what the GNU Project is, why it was created, its history and key components, its special relationship with Linux (hence the name “GNU/Linux”), the free software philosophy it introduced, and its lasting impact – including controversies and debates that have arisen along the way.

Table of Contents

Origins of the GNU Project and Richard Stallman’s Motivation

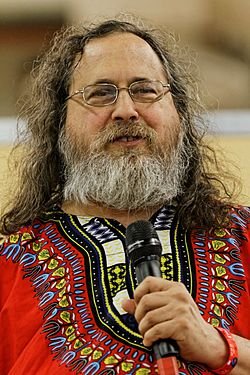

The GNU Project traces its origins to the early 1980s and the vision of Richard Stallman, then a software developer at MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Lab. Stallman announced the plan for GNU on September 27, 1983, declaring his intent to develop a free Unix-like operating system called “GNU” (a recursive acronym for “GNU’s Not Unix”).

The motivation was deeply rooted in Stallman’s experience at the MIT AI Lab, which in the 1970s had a thriving culture of sharing software source code. Programmers freely exchanged and modified each other’s code – an environment where software was a communal resource. Stallman recalls that in those days, although the term “free software” wasn’t yet used, the software was free in practice: anyone encountering an interesting program could ask for the source code and was typically given it without question.

This open culture began to collapse in the early 1980s due to a combination of commercial pressures and proprietary software restrictions. One oft-cited incident was “the printer story.” The AI Lab received a new Xerox laser printer, which frequently jammed. Stallman and his colleagues wanted to modify the printer’s software to notify users when it jammed, but they hit a roadblock: the printer’s driver was proprietary, supplied only as a binary with no source code available. Despite being capable programmers (they had built much of their own operating system software), they were “completely helpless to add this feature” because Xerox refused to share the source.

Frustratingly, the printer would sit jammed for long periods, wasting everyone’s time. When Stallman later found someone who had the source code (at Carnegie Mellon University) and asked for a copy, that person refused, saying he had signed a nondisclosure agreement – essentially choosing his proprietary obligation over helping fellow hackers. Stallman felt betrayed and “angry,” and this was a revelatory moment: he realized this was not just one bad actor, but a systemic problem with how software was becoming closed and controlled. As he later explained, “I saw not just an isolated incident, but a social problem” – the practice of withholding source code was destroying the cooperative spirit of computing.

By 1983, the situation had only worsened. The AI Lab’s old free-operating-system (the Incompatible Timesharing System) had become obsolete, and most new systems (like AT&T’s Unix) were proprietary. The hacker community Stallman had thrived in was effectively gone. In response, Stallman decided to fight back by creating a whole new operating system that would restore the freedoms hackers and users had lost.

He named it “GNU” as a nod to the Unix heritage but also to declare it wasn’t Unix – it would be free where Unix was not. As Stallman later stated, “with a free operating system, we could again have a community of cooperating hackers – and invite anyone to join”, allowing people to use computers without having to “start out by conspiring to deprive [their] friends” of source code and freedoms. In other words, GNU’s goal was to rebuild the communal, collaborative spirit of software development by giving everyone full control over their software.

On the symbolic date of Thanksgiving 1983, Stallman began coding. The initial GNU announcement outlined an expansive vision: “a complete Unix-compatible software system… and give it away free to everyone who can use it.” He described that GNU would initially include a kernel and all the utilities needed to write and run programs – editors, shell, compiler, linker, assembler – and then would add “everything useful that normally comes with a Unix system”.

In essence, GNU aimed to provide a whole operating system so that no one would need to use proprietary software for lack of a free alternative. Development officially kicked off in January 1984 after Stallman left his job at MIT to avoid any legal obstacles, dedicating himself fully to GNU.

The Core Principles of Free Software

From the outset, the GNU Project was not just a software endeavor but also a social and ethical initiative. Stallman defined the core principles of Free Software in terms of four essential freedoms that every computer user should have:

- Freedom 0: The freedom to run the program for any purpose.

- Freedom 1: The freedom to study how the program works and adapt it to your needs (which requires access to source code).

- Freedom 2: The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help others.

- Freedom 3: The freedom to improve the program and release your improvements to the public, so that the whole community benefits (again, requiring source code).

In short, software should respect users’ autonomy and community by allowing use, study, sharing, and modification. The term “free” in free software thus refers to freedom, not price – often explained by the phrase “free as in speech, not as in beer.” Anyone can charge money for distributing free software if they wish, but they cannot take away others’ freedom to further share or change it.

Stallman and GNU firmly asserted that these freedoms are rights, not mere privileges or conveniences. This philosophy was a departure from the emerging norm in the 1980s, where software companies treated programs as proprietary secrets and forbade sharing or tinkering. By publishing the GNU Manifesto in 1985, Stallman rallied others to the cause, explaining why software should be free and how an ecosystem of free software could thrive. He argued that cooperative sharing of software would lead to better quality and benefit society, and he rejected the notion that proprietary ownership of code was an ethical way to advance computing.

This stance laid the ideological foundation of what became known as the Free Software Movement, with the GNU Project at its center. In October 1985, Stallman also founded the Free Software Foundation (FSF) to support GNU’s development and to promote software freedom legally and organizationally. The FSF would handle tasks like raising funds, holding copyrights, and enforcing licenses for GNU software – allowing developers to focus on writing code while the foundation championed the cause in courts and public discourse.

Free Software vs. Open Source: What’s the Difference?

It’s worth noting the distinction between “free software” and “open source”, two terms often used interchangeably but born of different philosophies. Free software, as defined by GNU and the FSF, is an ethical stance emphasizing user freedoms and social solidarity. By contrast, the term open source was coined in 1998 by a group of developers as part of a marketing effort to make the idea of shared-source development more palatable to businesses. The Open Source Initiative (OSI) focuses on the practical benefits of sharing source code (such as improved quality, reliability, security, and cost savings) rather than the moral arguments.

While both free software and open source refer to software whose source code is available and can be modified and shared, the movements differ in focus. The free software movement (GNU/FSF) says that denying users the four freedoms is unjust, and thus insists on rights and principles. The open source movement tends to downplay talk of rights or ethics, instead promoting a development model they argue is more efficient and produces better software.

As Stallman succinctly put it, “Open source is a different movement” that “denies that this is an issue of principle”. He often laments that open source advocates invite companies to voluntarily open their code for practical benefits, whereas the free software camp maintains that users deserve these freedoms inherently.

Despite these philosophical differences, in practice the communities overlap significantly: they often work on the same projects, and most software that qualifies as free software also qualifies as open source under OSI’s definition. For example, the Linux kernel and GNU programs are both free software and open source. However, Stallman emphasizes the terminology because he wants people to think about freedom and user rights, not just collaborative programming. As a result, he “detests” being called an open source figurehead, preferring to be known for free software advocacy.

In summary, free software vs. open source is largely a matter of philosophy and messaging: free software is about defending ethical ideals of freedom, whereas open source is about promoting pragmatic benefits of openness. Both have been crucial in shaping today’s software landscape, but the GNU Project’s legacy lies firmly in the realm of free software philosophy.

Key GNU Components: Tools That Shaped Modern Computing

To build a complete free operating system, the GNU Project needed to create or collect a wide array of programs – essentially replicating or replacing everything a typical Unix system would have. This was a monumental undertaking, but over the years GNU succeeded in developing many core components that remain in widespread use. Here are some of the key GNU packages and what they do:

- GNU Compiler Collection (GCC): A family of compilers for many programming languages (C, C++, Fortran, Ada, and more). First released in 1987 as the GNU C Compiler, GCC quickly became a cornerstone of the free software ecosystem. It can target numerous hardware architectures and operating systems, making it invaluable for building software across platforms. GCC is not only the standard compiler on GNU/Linux systems but was also adopted by many other Unix-like OSes due to its quality. By providing a world-class compiler as free software, GCC enabled countless developers to compile their programs without needing proprietary tools – a crucial boost to the growth of free software. (Notably, the Linux kernel itself is compiled with GCC, and the compiler’s availability under the GNU GPL license gave kernel developers confidence their work would remain free.)

- GNU C Library (glibc): The standard C runtime library that programs use to interface with the kernel and perform basic functions (like input/output, memory management, string handling, etc.). Glibc is an implementation of the POSIX API and is a core part of any Unix-like system. The GNU C Library provides the essential language support and system call wrappers for GNU/Linux and other operating systems. In essence, if you write a C program on a Linux-based OS, glibc is what connects your program’s function calls to the underlying kernel. GNU’s glibc is used in almost all Linux distributions, making it a hidden backbone of countless applications.

- GNU Core Utilities (coreutils): A collection of basic Unix command-line tools such as cp (copy files), mv (move files), ls (list directory contents), grep (search text), chmod (change file permissions), and many more. These are the everyday commands users and scripts rely on in the shell. The GNU coreutils implemented the standard behavior of these commands (following POSIX standards), often with extensions and enhancements. Essentially, this package supplies the fundamental user-level utilities that one expects on any Unix-like system. Without coreutils, a “Linux” system would not have the familiar commands to manage files and directories. GNU coreutils ensured that all those commands were available as free software, allowing a GNU system to be functional and user-friendly from the get-go.

- GNU Bash (Bourne Again Shell): GNU’s command-line shell, which is the program that interprets user commands in text mode. Bash was written as a free replacement for the Unix Bourne shell (sh), incorporating features from other shells (like KornShell and C shell) and new improvements. First released in 1989, Bash became the default shell on most Linux distributions and even on Apple’s macOS for many users. If you’ve ever opened a terminal on a Linux system and seen a $ prompt, chances are you were using Bash. It allows users to run commands, write shell scripts to automate tasks, and interact with the system. By having Bash under the GNU umbrella, the project provided the principal user interface for text-based operations as free software.

- GNU Emacs: A powerful, extensible text editor that Stallman himself began developing in the mid-1980s (building on earlier ideas dating back to the 1970s). GNU Emacs is famed for its versatility – beyond editing text, it can function as a planner, email client, programming IDE, web browser, and more through a plethora of extensions. Emacs has been called “a great operating system, lacking only a decent editor” as a tongue-in-cheek reference to its endless customizability. It became one of the earliest and most popular GNU programs. Emacs is also notable for being one of the oldest free software projects still actively developed. It exemplified the GNU spirit: Stallman “invented” Emacs years before GNU, but by releasing GNU Emacs under a free license, he ensured this powerful tool remained available for all. Emacs, along with vi (another editor), was part of the classic “editor wars” in Unix culture, and GNU Emacs firmly established itself as a flagship of the free software toolkit.

- GNU Debugger (GDB): A robust debugger that allows software developers to see what’s happening inside a program as it runs (or when it crashes). GDB lets you set breakpoints, inspect variables, and step through code line by line. As part of GNU, it gave developers another essential tool under a free license, so they didn’t need proprietary debuggers for software development.

- GNU Make: A build automation tool that controls the compilation of programs. Most large software projects use make (with a Makefile) to efficiently compile and link code. GNU Make ensured this indispensable build system was free.

- GNU Hurd (Kernel): The kernel originally envisioned for the GNU system. GNU Hurd is a unique kernel architecture consisting of a collection of servers running on the Mach microkernel. Development of the Hurd began in 1990. However, Hurd turned out to be very complex and progressed slowly; it was not ready for mainstream use even years into the project. The delay of the Hurd opened the door for another kernel (Linux) to fill the gap (more on that in the next section). The Hurd is an example of GNU’s ambitions that proved technically challenging – it remains under development in a limited capacity to this day, but it never achieved the widespread adoption that the rest of GNU’s components did.

These are just a few of the hundreds of packages in the GNU Project. Others include GNU Coreutils (mentioned above), Findutils (for searching files), Binutils (assemblers and linkers for building programs), GLib (common programming library), GNOME desktop (a graphical desktop environment whose name originally stood for “GNU Network Object Model Environment”), and many more. Each of these components was crucial in replacing a part of proprietary Unix with a free equivalent. By the early 1990s, GNU had either built or collected nearly every piece needed for a complete operating system except one – and that was the kernel.

GNU and Linux: A Powerful Partnership (Why “GNU/Linux”?)

By 1990, the GNU Project had produced a vast array of tools and utilities, but its own kernel (the GNU Hurd) was still incomplete and not ready for everyday use. Meanwhile, in 1991, a Finnish student named Linus Torvalds independently created a Unix-like kernel as a personal project, which he named Linux. Initially, Linux was a small hobbyist kernel, but it caught on quickly with other developers. Importantly, in 1992 Torvalds released Linux under the GNU General Public License (GPL), changing it from a hobby project into a piece of free software that could be combined with GNU.

This was the magic moment: developers soon realized that GNU’s almost-complete operating system plus the Linux kernel would yield a fully functional, 100% free operating system. The GNU tools (compilers, shell, libraries, utilities, etc.) worked perfectly with the Linux kernel, since both were designed to be Unix-like. By combining Linux (the kernel) with the GNU system (the tools and user-space), the first entirely free software operating system came into existence.

Complete operating system distributions emerged in the early 1990s packaging Linux with GNU into one installable system – for example, Debian GNU/Linux (whose founders explicitly embraced GNU’s ideals) and others like Slackware, Red Hat, etc. Millions of users started to use these systems, typically referring to them simply as “Linux” (after the kernel).

However, Stallman and the FSF have long argued that it’s more accurate to call the system “GNU/Linux” because the kernel alone is not a full operating system – it’s the combination of GNU components with the Linux kernel that gives users a working OS. In their view, GNU’s contribution was enormous and acknowledging it in the name gives credit to the free software movement’s ideals that made the whole thing possible.

To understand this, consider that if you open a terminal on a typical “Linux” distribution and run –version commands, you’ll find GNU Coreutils for basic commands, the GNU Bash shell, GNU tar, GNU compiler, GNU C library, etc. The userland (everything above the kernel) is predominantly GNU. The kernel (Linux) itself is just one program – albeit a very important one that manages hardware and low-level resources.

The FSF thus calls such systems GNU/Linux. They also note that GNU and Linux are usually “combined” in this way on millions of servers, desktops, and devices, forming the backbone of the internet and modern computing. In fact, the GNU+Linux combo is so pervasive that it powers everything from web servers to Android phones (Android uses the Linux kernel and some GNU userland tools, though not GNU libc).

Nonetheless, most of the world simply says “Linux” for these systems, and this has led to a long-running naming controversy. Stallman’s insistence on “GNU/Linux” is sometimes seen as pedantic or political. Many developers (including Linus Torvalds) feel that the name “Linux” in common usage refers to the whole system and adding “GNU” is unnecessary. Torvalds once commented that while you could call a specific distribution “GNU/Linux” (just as you might say “Debian Linux” or “Red Hat Linux”), “calling Linux in general GNU/Linux is just ridiculous”.

He suggested that whoever puts together a distribution gets to name it – and since people outside FSF built many distributions, they chose the simpler name. Additionally, others point out that modern Linux-based OSes include many components that are neither Linux nor GNU (for example, graphical environments like KDE, browser like Firefox, etc.), so singling out GNU in the name may seem unfair to other contributors. As the Jargon File (a hacker dictionary maintained by Eric S. Raymond) quipped, the argument over nomenclature “is a proxy for an underlying territorial dispute” about credit, and indeed Stallman “and friends” wrote many parts of the system, but the term GNU/Linux has only “gained minority acceptance.”

Despite the debate, the relationship between GNU and Linux is symbiotic and historically significant. Linux provided what GNU lacked (a kernel) at just the right time, and GNU provided Linux with a complete operating environment and philosophical grounding. This partnership gave birth to the operating systems that have revolutionized computing – everything from web servers, supercomputers, IoT devices, to your Android phone likely runs on the GNU/Linux model. Some in the community choose to use the combined name (GNU/Linux) to honor that partnership and highlight the ideals of free software behind it.

For instance, the Free Software Foundation Europe explicitly asks people to say “GNU/Linux” so that new users hear about GNU and the goal of software freedom, not just “Linux” in isolation. In this article, we’ve generally referred to the whole system as “Linux” or “GNU/Linux” contextually, but it’s good to understand why that slash is sometimes there. It’s a reminder that Linux (the kernel) alone would not have thrived without GNU’s userland, and likewise ,GNU’s mission would have taken much longer to reach the masses without Linux’s kernel. Together, they fulfilled the GNU Project’s original aim: to provide a completely free operating system for everyone.

The GNU General Public License (GPL) and Copyleft

A critical part of GNU’s impact comes from its approach to licensing, in particular the creation of the GNU General Public License (GPL). The GPL, often called just “the GPL”, is far more than legal boilerplate – it’s the embodiment of GNU’s philosophy in legal form. It was the first copyleft license written for general software use, originally authored by Stallman (with help from legal scholars) for the GNU Project.

What is copyleft? In simple terms, copyleft is a licensing principle that uses copyright law to ensure freedom rather than restrict it. A copyleft license like the GPL grants everyone permission to use, copy, modify, and redistribute the software (the freedoms of free software) on the condition that any redistributed or derivative version is also licensed under the same terms. This means you can’t take GPL-covered code, change it, and then release your modified version as proprietary software – if you distribute the modified version at all, you must grant the same freedoms to its users. In effect, copyleft keeps software free by preventing someone from taking a free program and turning it into a closed-source, proprietary product.

Stallman often analogized copyleft to “giving the software freedoms teeth”. The GPL enforces the “share alike” requirement: if you benefit from the community’s open code, you must contribute back under the same open terms. This was a novel idea in the 1980s. Most earlier free software (such as it existed) was public domain or under very permissive licenses that allowed proprietary forks. The GPL was deliberately written to be hereditary: to propagate freedom forward. As the license text states, it grants recipients “the rights of the Free Software Definition” – essentially the four freedoms – and in exchange requires that any distribution of the software or derivative works preserve those rights by using the GPL again.

The initial version, GPLv1, came out in 1989. It was followed by GPLv2 in 1991 (this is the famous license that Linux kernel adopted). In 2007, after a long community consultation process, GPLv3 was released to address new issues like software patents and “Tivoization” (hardware manufacturers using GPL software but locking down devices so users can’t run modified versions on them). All versions of the GPL maintain the core copyleft principle. The license is often summarized by the slogan: “free software” is free not as in price, but in freedom, and copyleft makes sure it stays that way.

One effect of the GPL was to give developers confidence that contributing to a GPL-licensed project wouldn’t result in their work being co-opted by a company without giving back to the community. For example, many believe the success of Linux was partially due to the GPL: developers knew that any improvements they made to the Linux kernel would remain available to everyone, rather than being absorbed into a proprietary version owned by some corporation.

In the 1990s, this was a compelling incentive – it created a sort of virtuous cycle of contributions. The GPL became (and remains) one of the most widely used software licenses in the world. Major projects under GPL include not just GNU packages but also the Linux kernel itself, MySQL database, and countless others.

It’s important to note that the GPL does not forbid selling software – on the contrary, it explicitly allows commercial sale – but it does ensure that whoever you sell it to can subsequently share it or modify it. This has led to sustainable business models (like support contracts, dual-licensing, etc.) without compromising user freedom. The GPL also doesn’t infect other code unintentionally: it only applies if you distribute the GPL-covered code or a derivative. Developers can also link GPL code with other code under certain conditions (for example, using the LGPL, a weaker copyleft for libraries, or via explicit runtime exceptions).

Over the years, some criticism has been levied at the GPL from those who prefer more permissive licenses (like MIT or BSD licenses). Permissive licenses allow others to reuse code in proprietary programs, which some argue encourages wider adoption by industry. Proponents of permissive licenses sometimes call the GPL “viral” or “too restrictive” because it forces all combined code to be GPL as well. Stallman’s view, however, is that those “restrictions” are what protect user freedoms; without copyleft, companies could gradually proprietize the commons. This debate is “open source vs. free software” in another guise – pragmatic freedom to do anything (even make something proprietary) versus ethical insistence that freedom be preserved.

Regardless of one’s stance, there is no doubt that the GNU GPL has had a profound impact. It pioneered the legal framework for free software and inspired other copyleft licenses (and even Creative Commons licenses for art/content). The term “copyleft license” is now common parlance, and the GPL remains the clearest example of one. Indeed, the GPL is often referred to as the constitution of the free software movement – a foundational document ensuring that GNU’s software (and any software that adopts the license) carries forward the movement’s ideals wherever it goes.

Milestones in GNU Project History

The GNU Project’s journey spans several decades. Here are some key milestones and evolution points in its history:

- 1983 – The GNU Project is announced: Richard Stallman posts the “initial announcement” of GNU on September 27, 1983, outlining his plan to create a free Unix-like OS called GNU. This date is now considered the birth of the Free Software Movement.

- 1984 – Development begins: In January 1984, Stallman quits his job at MIT to work on GNU full time. He also starts writing foundational software like GNU Emacs. Early contributions from volunteers worldwide begin coming in as well.

- 1985 – Free Software Foundation established: Stallman founds the FSF in October 1985 to support GNU. That year he also publishes the GNU Manifesto (March 1985 in Dr. Dobb’s Journal), rallying others to the cause. GNU Emacs is released under a precursor to the GPL. By this time, GNU already has a working text editor (Emacs), and other tools are under development.

- 1987 – GCC 1.0 released: The GNU C Compiler (later renamed GNU Compiler Collection) releases version 1.0. GCC’s quality and usefulness quickly attract a broad user base. By June 1987, GNU has an assembler, linker, debugger, and an almost finished C compiler, along with many Unix-like utilities (ls, cp, grep, etc.).

- Late 1980s – GNU grows: Development continues on multiple fronts. The GNU Debugger (GDB) is released. Work begins on the GNU C Library (glibc) and other system components. By the end of the ’80s, GNU has most of the components of an OS except the kernel.

- 1989 – GNU General Public License v1: FSF publishes the GPL version 1. This formalizes the copyleft approach. Also in 1989, the first program under GPL (GNU Chess, interestingly) is released. The New York Times publishes an article “One Man’s Fight for Free Software” about Stallman, spreading awareness of GNU.

- 1990 – GNU Hurd kernel work intensifies: GNU’s original kernel attempt, the Hurd, is launched to replace the temporary kernel (TRIX/Mach). However, it proves difficult to implement. (The microkernel approach the Hurd uses is complex, and progress is slow.) This delay sets the stage for Linux to step in.

- 1991 – Linux kernel is created: Linus Torvalds releases version 0.01 of the Linux kernel (not yet free software). Separately, in 1991 FSF releases GPL version 2, slightly updating the license terms.

- 1992 – Linux relicensed under GPL: Torvalds adopts the GPLv2 for Linux. This is a game-changer: Linux and GNU can now legally be combined. Around 1992, the combination of Linux kernel with GNU’s operating system utilities produces the first working GNU/Linux systems. The Debian project is founded in 1993 (with FSF support) to create a GNU/Linux distribution committed to free software principles.

- Mid-1990s – Explosion of GNU/Linux distributions: Various groups package GNU/Linux into easy-to-install distros. Examples: Slackware (1993), Red Hat (1994), SUSE (1994), etc. The technology starts being used in servers widely. The term “Linux” starts to become known in the tech world, often overshadowing the name GNU. Meanwhile, GNU continues to develop new components (e.g., GNOME desktop starts in 1997 as a GNU project to provide a fully free desktop environment when KDE had reliance on a proprietary Qt toolkit).

- 1998 – “Open Source” term and Mozilla code release: Netscape announces the release of its browser code (Mozilla) as open source, and the term “open source” is coined as a more business-friendly label for free software. This creates some tension; the movement splits into Free Software (GNU/FSF) vs Open Source (OSI) camps, though they collaborate on many practical projects. GNU and FSF double down on emphasizing the ethics of free software to differentiate from the new rhetoric.

- 2001 – GNU/Linux gains mainstream notice: The GNU/Linux system (often just called Linux) is now used to run major internet servers and infrastructure. The “dot com” boom of the late ’90s was built in part on free software like GNU/Linux and Apache web server. In 2001, Microsoft’s CEO famously calls Linux “a cancer” (referring to the GPL’s copyleft) – underscoring that GNU/Linux had become a real competitor to traditional proprietary software models.

- 2002 – GNU FDL and Wikipedia: The GNU Free Documentation License (FDL) is used by Wikipedia in its early years, showing GNU’s influence beyond software.

- 2007 – GPL version 3: After several years of drafts and public discussion, GPLv3 is published. It addresses new issues such as software patents, DRM, and hardware tivoization (where devices prevent users from running modified software). The update is somewhat controversial – for instance, Linus Torvalds chooses to keep the Linux kernel on GPLv2 only, disagreeing with some changes. Nonetheless, many projects migrate to GPLv3, and it becomes another widely used license alongside GPLv2.

- 2010s – Ubiquity of GNU/Linux and continuing advocacy: Free software is everywhere, often under the radar. Android (smartphone OS) uses the Linux kernel (albeit with many non-GNU components). Most web servers run GNU/Linux. The collaborative development model is adopted even by companies (open source on GitHub becomes common). FSF and Stallman continue to campaign against new threats to freedom: DRM (“Defective by Design” campaign), software-as-a-service (which Stallman calls “SaaSS” and warns can deprive users of control over software on servers), and locked-down computing (like Apple’s walled garden). The free software movement also inspires movements in hardware (open hardware designs, RISC-V, etc.) and culture (Creative Commons licenses for creative works). In 2013, GNU celebrates its 30th anniversary; by this time, terms like FOSS (Free and Open Source Software) are mainstream in IT.

- 2019 – Leadership changes and controversies: In September 2019, Richard Stallman resigns as president of the FSF and leaves his role at MIT after controversy around comments he made regarding an MIT-related scandal. This incident brings to light some long-standing criticisms of Stallman’s personal behavior and statements, separate from his software work. The FSF faces internal and external calls to reform.

- 2021 – Stallman returns and community debates: In March 2021, Stallman announces he has rejoined the FSF’s Board of Directors, catching many (including some FSF staff and board members) by surprise. This move sparked outrage among some in the tech community and led to an open letter from dozens of organizations calling for reform at the FSF and Stallman’s removal. It also prompted a counter-letter of support from some free software enthusiasts. The episode underscored the generational shift and the question of how the Free Software Foundation should evolve beyond its founder.

- 2023 – 40 years of GNU: The GNU Project marked its 40th anniversary on September 27, 2023. Events and hacker meetups celebrated four decades of free software activism. The FSF used this occasion to highlight that software freedom is still highly relevant: even though free software won many battles (with open-source now a common development model), new challenges in cloud computing, device lockdown, and digital rights management mean the fight for user freedom continues. The GNU Project remains active, maintaining its many packages and even the long-running GNU Hurd kernel (which, though not widely used, saw new releases). The volunteer developers and maintainers of GNU packages around the world carry on the work begun in 1983.

This timeline shows how GNU started as an almost quixotic endeavor by one man, grew into a collaborative global project, catalyzed the creation of Linux-based operating systems, and influenced the entire software industry. It’s a history intertwined with the rise of the Internet and the open-source revolution, even as GNU’s staunch activists remind us to not lose sight of the original ethical goals.

Impact and Legacy of GNU on the Tech World

The impact of the GNU Project on today’s technology landscape is hard to overstate. GNU turned the idea of free software from a fringe notion into a powerful movement that changed how software is developed and distributed. Here are some of the key aspects of GNU’s legacy:

- Establishing the Free Software Movement: GNU was the spark that ignited a broad social movement around software freedom. It brought issues of user rights and ethics into the conversation. Terms like “Free Software”, “Copyleft”, and even “Open Source” (as a reaction) likely wouldn’t exist in the mainstream without GNU’s pioneering role. Stallman’s philosophical framework (the four freedoms, etc.) remains a reference point in debates over digital rights, from software to media. Even people who don’t agree with all of Stallman’s positions have been influenced by the questions GNU raised: Who should control software – its creators or its users? What do we lose when software is proprietary? These discussions continue in modern forms (e.g. debates over cloud services, data privacy, and app store restrictions).

- Empowering the Open-Source (FOSS) Development Model: GNU not only advocated for software freedom, but also produced high-quality software that proved the viability of collaborative development. The success of tools like GCC, GNU/Linux, etc., demonstrated that volunteers and companies could co-create complex software outside of a traditional proprietary model. This directly paved the way for the broader open-source ecosystem we see now, where companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft open-source significant projects, and where millions contribute to free software on platforms like GitHub. The fact that today open source is everywhere – in operating systems, programming languages, libraries, frameworks – owes a great deal to GNU’s early example and insistence on sharing source code. As FSF’s executive director Zoë Kooyman said in 2023, “when we look back at the history of the free software movement… it starts with GNU”, and GNU is “at the core of a philosophy” that has guided this movement for decades.

- Linux and the Server/Internet Revolution: Without GNU, there likely would be no “Linux” as we know it. The pairing of GNU userland with the Linux kernel made the open-source Unix revolution possible. This combination (often simply called Linux) runs a majority of web servers globally, forms the basis of Google’s Android OS (billions of devices), and drives infrastructure from supercomputers to cloud computing. In essence, GNU provided the heart (user environment and tools) and soul (philosophy) of what became a new paradigm in software. The backbone of the modern Internet – from the Apache/Nginx web servers to the GNU/Linux servers at Amazon, Google, Facebook, etc. – descends from GNU’s decision to make an operating system freely available to everyone. Even Microsoft, once a fierce critic, runs Linux systems on Azure and has embraced open-source development in many areas, a testament to the model GNU helped pioneer.

- Quality and Ubiquity of GNU Software: Many GNU programs set high-water marks for quality and utility. GCC, for example, became one of the most important compilers in the world. Bash became synonymous with command-line shell for millions of users. Emacs influenced generations of developers and inspired other extensible editor projects. The GNU scientific library, GNU Octave (math software), GNOME desktop – all these fill important niches. In the 1990s, having free (libre) tools of this caliber lowered barriers to entry for students, startups, and developers everywhere. No longer did one need to buy an expensive Unix license or proprietary compiler to learn programming or set up a server – GNU software provided a cost-free (and freedom-respecting) alternative. This democratization of software tools contributed enormously to innovation and education worldwide.

- Spreading to Other Domains: GNU’s idea of copyleft licensing spread beyond software. Creative Commons licenses (introduced in 2002 for art/content) include ShareAlike variants that mirror copyleft. Wikipedia initially used GNU’s Free Documentation License for its content, later switching to CC-BY-SA (which is essentially copyleft for text). The ethos of sharing and collaborating, under rules that keep content open, owes something to GNU’s trailblazing. We also see “open hardware” projects (like OpenCores, or RISC-V instruction set, etc.) and open data projects that draw on similar principles.

- Catalyst for Legal and Academic Inquiry: The GNU Project prompted serious legal scholarship around copyright, licensing, and intellectual property. The GPL was something novel for lawyers – essentially a copyright license that uses copyright to insist on openness. Over the years, case law has developed around enforcing the GPL. The existence of organizations like the Software Freedom Law Center, and discussions about how copyright intersects with digital goods, trace back to the groundwork GNU laid. Academically, GNU and FSF’s stance fueled a rich discussion on ethics in technology that continues (e.g., discussions about user agency, right to repair, etc.).

However, GNU’s legacy is not without criticisms and controversies, which we’ll address in the next section.

Controversies and Criticisms

Throughout its history, the GNU Project and its founder have encountered various controversies. Some are debates of terminology and credit, while others relate to personal or organizational issues. Here are a few notable ones:

- The GNU/Linux Naming Debate: As discussed earlier, what to call the operating system that combines GNU and Linux has been a point of contention. Stallman and the FSF strongly advocate the term GNU/Linux, arguing that it educates users about the system’s origins and the principle of freedom it stands for. Critics, however, sometimes view this as an attempt to grab credit or as confusing political correctness. The Jargon File entry famously framed it as a “territorial dispute,” suggesting that FSF wanted more credit for GNU’s contributions, but also noting that “neither this theory nor the term GNU/Linux has gained more than minority acceptance” in the community. Linus Torvalds, when asked if GNU/Linux was justified, said “it’s justified if you actually make a GNU distribution of Linux… but calling Linux in general ‘GNU Linux’ I think is just ridiculous.” He felt that people can call their own distro what they like, but it’s needless to apply GNU/ prefix to everything using Linux. Furthermore, prominent voices like developer Jim Gettys pointed out that a typical Linux-based OS includes many components (from X Window System to various apps) that are neither GNU nor Linux, so singling out GNU above others might not reflect the collective effort involved. On the other hand, supporters of Stallman argue that without GNU there wouldn’t have been a complete system to marry Linux to, and that calling it just “Linux” erases the history and philosophy behind it. This debate has sometimes been heated, but in practice it settled into a kind of equilibrium: the majority say “Linux” for brevity, while FSF circles and some distributions (like Debian or Trisquel) use GNU/Linux in recognition of GNU’s role. It’s a unique quirk of tech nomenclature that arguably no other software project has a naming controversy quite like this!

- Stallman’s Personal Controversies: Richard Stallman (often nicknamed RMS) is a brilliant and uncompromising figure, but his very uncompromising nature and some personal eccentricities have led to controversy. Over the years, he’s made statements or taken stances that many found extreme. For example, Stallman consistently refuses to use any proprietary software at all – he doesn’t own a smartphone (because phones require nonfree firmware), and he browses the web with a text-based browser to avoid nonfree JavaScript on websites. While these choices align with his principles, they are impractical for most and have sometimes made him seem out of touch. More seriously, Stallman has been criticized for comments on unrelated matters (such as sexual misconduct cases, terminology about pedophilia, etc.), which came to a head in 2019. Emails he wrote regarding the MIT Epstein scandal were viewed as insensitive, sparking a public outcry. As a result, Stallman resigned from his long-time leadership role at FSF in 2019. NPR noted that despite his status as “the godfather of the free software… movement,” he had “long cut a divisive figure for his personal views.”. Then in 2021, his return to the FSF board reignited the controversy and led some major organizations (like the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Red Hat) to distance themselves from FSF. This saga has cast a shadow on FSF/GNU, with some wondering if the movement’s image has been tarnished by association. Others defend Stallman, arguing that however impolitic he can be, his role in launching free software remains monumental and that the campaign against him was overblown. Regardless, it’s clear the GNU Project’s leadership has been a topic of contention, and it raises the question of how GNU/FSF can carry forward its mission with or without Stallman at the helm.

- “Cathedral vs Bazaar” and Pragmatism vs Idealism: In the late 1990s, a schism in the community appeared symbolically in the form of Eric S. Raymond’s essay “The Cathedral and the Bazaar” (1997) which praised the open-source development model used in projects like Linux (the “bazaar” style of open collaboration) versus the more controlled “cathedral” style he associated with GNU and FSF. Raymond and others formed the Open Source Initiative (OSI) and deliberately downplayed the moralistic language that Stallman used. Some viewed the OSI vs FSF dynamic as a criticism that GNU was too ideological and not welcoming to commercial or pragmatic considerations. GNU in turn criticized “open source” as missing the point about freedom. While not a direct controversy in the sense of a scandal, this philosophical divide did cause some friction. For example, when companies started embracing open source in the 2000s, they often did so under the OSI banner, occasionally painting FSF as radical. To this day, debates rage on topics like whether copyleft (GPL) is better or worse than permissive licenses, whether FSF’s hardline stance on things like DRM is productive or alarmist, etc. The “open source vs free software” narrative is essentially a debate over how best to advocate for essentially similar sets of licenses. GNU’s side of that debate sometimes gets criticized as impractical or overly purist; on the flip side, FSF would criticize the open-source camp for lacking spine or concern for user rights.

- GPL Enforcement and GPLv3 backlash: Another controversy touches the GPL itself. As the GPL grew in use, enforcing it when violated (e.g. a company using GPL code in a product but not releasing source) became an important task. Organizations like the Software Freedom Conservancy have pursued legal action to enforce the GPL. While many see this as necessary (to uphold the license’s terms), others in the community, including Linus Torvalds, have sometimes expressed discomfort with lawsuits. Torvalds favored a community approach to enforcement – he once said he doesn’t sign copyright assignment for FSF because he didn’t want GPL enforcement lawsuits done in his name. Moreover, when GPLv3 was being drafted, some (especially in the Linux kernel camp) strongly opposed certain provisions (like patent retaliation clauses or anti-DRM measures). They saw it as FSF pushing its political agenda (e.g., anti-DRM) through the license, potentially at the cost of adoption. The Linux kernel stayed with GPLv2, and today the ecosystem is split between GPLv2 and GPLv3 projects. This was a rare instance where a GNU initiative (updating the GPL) faced visible pushback from key open source leaders.

In summary, the GNU Project’s controversies often stem from its uncompromising commitment to principles and the personality of its founder. The naming issue is about credit and philosophy, the movement split is about how to pitch those principles, and the personal issues around Stallman highlight the challenges any social movement faces as it grows and its founder’s behavior is scrutinized. Despite these wrinkles, GNU’s core ideas have endured. Even critics who find Stallman difficult will often acknowledge that his work was pivotal. And even those who don’t say “GNU/Linux” will concede that Linux systems owe a huge debt to GNU.

Conclusion: The Continuing Relevance of GNU Today

After more than 40 years, the GNU Project remains as relevant as ever – not just through the software that literally runs the modern world, but through its enduring message about freedom and user rights. Every time you use a device or software, the issues GNU raised come into play: Do you control that technology, or does someone else?

GNU’s mission was to ensure that users, not just producers, have control, and that mission isn’t finished. In fact, as software has permeated every aspect of life, from smartphones to cloud services, one could argue (as the FSF did on GNU’s 40th anniversary) that “GNU and free software are even more relevant” now because “the vast majority of users do not have full control” over the software in their lives.

The GNU Project’s software continues to be foundational. Updates and new releases for GCC, glibc, Emacs, coreutils, and dozens of other packages roll out, maintained by a dedicated community of free software developers. New projects under GNU are still started (for example, Guix, a package manager and Linux distribution, or GNU Jami, a peer-to-peer communication platform). The Free Software Foundation and its sister organizations (like FSF Europe, FSF India, etc.) continue advocacy and public campaigns – whether it’s lobbying for legislation to protect the right to install your own software on devices, or sponsoring conferences like LibrePlanet to bring together activists.

GNU’s principles have also influenced discussions around privacy and security. The idea that users should be able to examine what their software is doing (for trust reasons) ties into today’s concerns about spyware and data collection. GNU was talking about “malicious features” in software long before the average user became aware of concepts like telemetry or backdoors. Now, with growing public awareness of Big Tech’s power, GNU’s call for software transparency and user empowerment resonates with movements for digital rights at large.

In the realm of education and developing economies, GNU (and Linux) have made it possible to learn computing without expensive software licenses, fostering local tech development and saving costs. Governments and companies leverage free software because it gives them independence and flexibility. All this can be traced back to the GNU Project’s groundwork.

It’s true that the spotlight in recent years has often moved to “open source” and giant collaborative projects (like the Linux kernel, or Kubernetes, etc.) where the emphasis is less on philosophy. But the heart of Linux is still GNU – not just in the technical sense of GNU components, but in the sense that the free software ethos underpins why a global community can collaborate on Linux in the first place. The DNA of the GNU Project is present in every open-source license, every Git repository that welcomes contributions, and every user who can install a program and tinker with it to suit their needs.

As we look to the future, the GNU Project reminds us that technology should serve its users, not bind them. Whether it’s called free software or open source, the idea that collaboration and freedom create better software and a better society is GNU’s gift to the world. In a 2023 reflection, the FSF stated that GNU is both a technical project and “the core of a philosophy” guiding the movement. That philosophy – advocating user freedom, community cooperation, and ethical technology – continues to inspire new generations.

In conclusion, the GNU Project stands as the foundation of free software and, indeed, the ideological heart of what many simply call the Linux ecosystem. Its creation marked a turning point in computing history, proving that an alternative to proprietary software not only could exist, but could excel and change the world.

Despite challenges and controversies, GNU’s legacy is secure: it gave us the tools, the licenses, and the principles that have made software more accessible and equitable for all. And as long as software plays a role in our lives (which it certainly will for the foreseeable future), GNU’s core message – “software freedom is important” – will remain vitally important, guiding us toward a future where users truly have control over the technology they rely on.