The MCM/70 microcomputer was a groundbreaking device born in the early 1970s – a full decade before the IBM PC – yet it remains a largely forgotten pioneer in the history of microcomputers. Conceived and built in Canada in 1973, the MCM/70 was one of the world’s first personal computers and arguably the first truly portable computer designed for general use. It packed innovative features like a built-in one-line plasma display, cassette tape storage, and the advanced APL programming language into a compact desktop unit.

MCM/70’s creators envisioned bringing interactive computing to individuals in business, education, and science at a time when room-sized mainframes dominated computing. Two years before Bill Gates formed Microsoft and three years before the Apple I, a small Toronto company had produced a personal microcomputer they believed could launch a revolution. Despite its “ahead of its time” technology and vision, the MCM/70 was overshadowed by later American PCs and largely forgotten outside of tech historian circles. This article revisits the MCM/70 – its origins, features, successes, struggles – to illuminate why it deserves recognition as a forgotten pioneer of personal computing.

Table of Contents

A Canadian First in the Early Era of Microcomputers

The MCM/70 holds a special place in Canadian computing history. It was developed by Micro Computer Machines (MCM) of Toronto and officially unveiled on September 25, 1973 at the Royal York Hotel. This timing made it one of the very first commercially available microcomputers in the world. In fact, the MCM/70 is often cited as the second microcomputer ever shipped fully assembled (after the French Micral) and the first portable personal microcomputer.

Unlike hobbyist-oriented kits that would come later, the MCM/70 was sold as a ready-to-use “desk top computer” for end users. Electronics Communicator magazine noted at the time that “Canada has stolen an early world lead in the new era of ‘distributed processing’ which will bring the dream of a computer in every home and office closer to reality.” In other words, a Canadian company had beaten much larger U.S. firms to the punch in offering a personal microcomputer.

Historical context: When the MCM/70 was introduced, personal computing was still an unformed idea. Competing claims for the “first personal computer” include devices like the Kenbak-1 (1971, not microprocessor-based) and the Micral (1973, a French industrial microcomputer). Still, these were either limited in capability or not intended for the general public. The MCM/70, by contrast, was designed from the start for personal use by individuals. It arrived before the famous MITS Altair 8800 (1975) and years before the Apple I (1976), yet it already offered features those early hobbyist machines lacked.

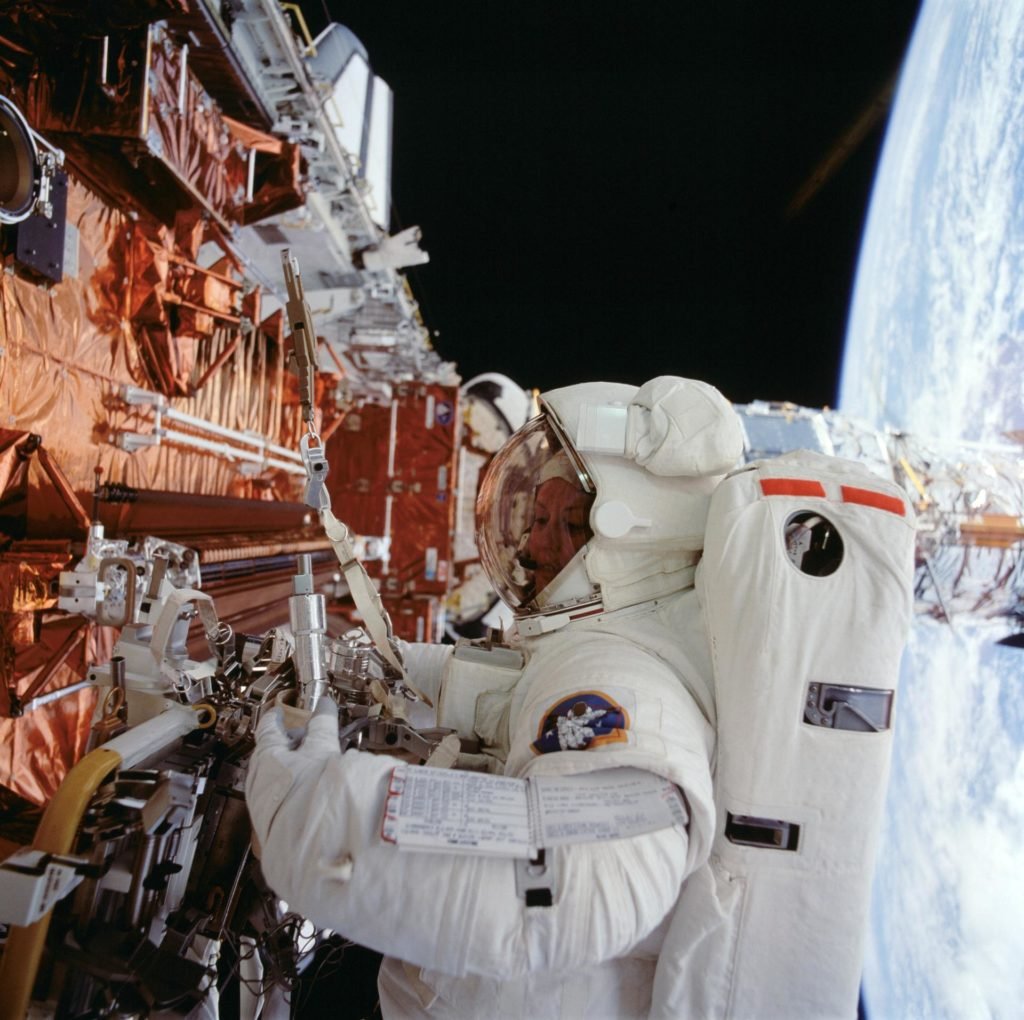

For instance, by the time the Altair kit with its 256 bytes of RAM (and no high-level programming language) hit the market in early 1975, MCM’s microcomputer was running interactive software for real engineering, business, and educational applications. By the time Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak were selling the Apple I board in 1976, the MCM/70 was in use at organizations like Chevron Oil, Firestone, the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children, Mutual Life New York, Ontario Hydro, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and even the U.S. Army. This impressive roster of early users underscores how advanced the MCM/70 was compared to its contemporaries.

Early 1970s: Vision and Development of the MCM/70

The story of the MCM/70 begins with Mers Kutt, a visionary Canadian computer scientist and entrepreneur. In the late 1960s, Kutt was a mathematics professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. He observed firsthand how inefficient computing access was – students and researchers had to submit programs on punched cards and wait in line for batch processing on a shared mainframe. Determined to improve this, Kutt co-founded a company in 1968 called Consolidated Computer Inc. (CCI), which produced a product named Key-Edit.

Key-Edit was essentially a smart terminal with a one-line display that allowed users to type data directly (and correct errors easily) instead of using keypunch cards. The device was a hit, with over 30,000 units installed worldwide, demonstrating Canada’s burgeoning tech prowess. However, internal conflicts led to Kutt being forced out of CCI in 1971, just months after his wife’s death.

Undeterred, Mers Kutt set his sights on an even more ambitious goal: a “scaled down computer for personal use”, spacing.ca. In 1971, he founded a new venture called Kutt Systems and soon began sketching ideas for a small, interactive computer. Crucially, Kutt was fascinated by a new programming language called APL (A Programming Language), which had been developed at IBM in the 1960s. APL was powerful for mathematics and engineering but usually ran only on big IBM mainframes and required a special character set.

Kutt envisioned a machine that could bring APL computing to individuals, giving them mainframe-like capabilities on a desktop. He initially dubbed the concept “Key-Cassette” – building on his earlier Key-Edit terminal idea by adding the ability to edit, store, and run programs on cassettes rather than submitting jobs to a distant mainframe.

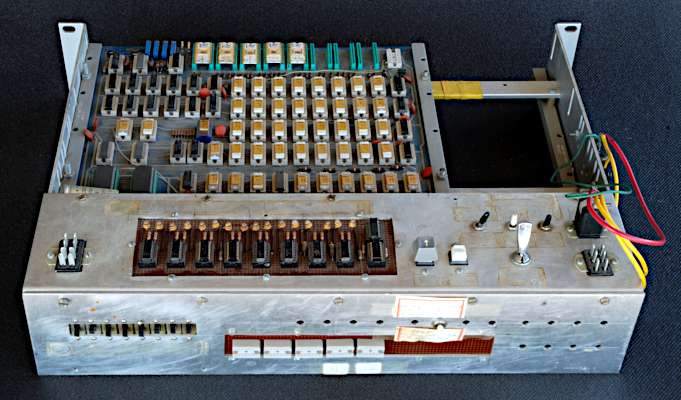

To turn this vision into reality, Kutt leveraged his connections in the nascent microprocessor industry. Through an acquaintance with Intel co-founder Robert Noyce, he kept tabs on Intel’s first 8-bit microprocessor project (the 8008) in 1971. He even obtained an Intel 4004-based development system while waiting for the 8008 to be released. By May 1972, once Intel’s SIM8-01 kit with the new 8008 CPU became available, Kutt’s small team got to work building a prototype. This early team included hardware engineer José Laraya, programmer Gordon Ramer, software engineer André Arpin, and APL specialists Don Genner and Morgan Smyth. Working out of Kingston and Toronto, they nicknamed the project the “M/C” (short for micro-computer).

Laraya quickly designed a rack-mounted prototype with an Intel 8008 processor, some RAM and EPROM memory boards, and a one-line Burroughs plasma display (an orange-glowing 32-character panel) interfaced to a small custom keyboard. By mid-1973, Ramer and Genner had successfully ported a subset of the APL language into the prototype’s ROM chips, allowing the machine to actually run APL programs.

The first test calculation – “1 + 1” – was a modest milestone, but on this tiny system, it took a few seconds to compute! As Laraya recalled, “you did 1+1, and it took forever (a few seconds) to crunch out the number”, with the team watching numbers flicker on the small display as the calculation progressed. Performance was slow at first, but it was fascinating proof that APL could run on a microprocessor with only a few kilobytes of memory.

Throughout 1972–73, the hardware and software were refined in tandem. York University’s computing center in Toronto became an important resource – Ramer had been using APL there and even created a simplified APL interpreter called York APL that could fit in a smaller memory footprint. This work became the basis for the MCM/70’s own APL system. The fledgling company, now incorporated as Micro Computer Machines Inc., secured funding and forged ahead.

By May 1973, they felt confident enough to demonstrate a working prototype of the MCM/70 at the Fifth International APL Users’ Conference in Toronto. Showing off a “portable APL machine” to the APL community was a bold move – and it generated buzz. (One attendee later quipped that “lugging the MCM home on the subway in New York helped build up my muscles, as it was hardly a lightweight”, underscoring that “portable” was a relative term for this ~20-pound device!)

Mers Kutt and André Arpin – The People Behind the Machine

The creation of the MCM/70 was very much a team effort, but two individuals stand out: Mers Kutt and André Arpin.

Mers Kutt was the charismatic driving force and visionary behind MCM. Born in Winnipeg, he was a professor-turned-entrepreneur with a knack for tackling “impossible” projectsspacing.ca. Kutt’s leadership and belief in personal computing were instrumental in guiding the MCM/70 from idea to product. He not only founded MCM and oversaw the project, but also evangelized the concept of personal microcomputers years before it became mainstream. During the MCM/70’s introduction, Kutt boldly predicted a future “filled with millions of small computers, just like the MCM/70, and only a limited number of large ones.”

This prescient vision — essentially foreseeing the PC revolution — was uttered in 1973, long before others saw microcomputers as more than toys. Kutt has since been hailed by some as “the father of the PC” in Canada, though his name is far less famous than contemporaries like Steve Jobs or Bill Gates. Humble about his legacy, Kutt told a reporter in 2006, “You don’t think of [making history] particularly when you’re developing it, you just do something you think is pretty neat.”spacing.ca

André Arpin played a crucial behind-the-scenes role as MCM’s software and systems architect. A talented computer engineer, Arpin joined the project in early 1972 and became one of the key designers of the MCM/70’s internal architecture. He was an APL expert who helped implement the APL interpreter that ran on the 8008 processor. In particular, Arpin wrote the floating-point arithmetic routines that allowed the MCM/70 to handle numerical calculations with 16-digit precision – an impressive feat on an 8-bit CPU. Perhaps Arpin’s most ingenious contribution was designing the MCM/70’s virtual memory system, known as AVS (for “A Virtual System”).

AVS, written by Arpin, used one of the machine’s cassette tape drives as an extension of memory, swapping data between RAM and tape automatically.

This gave the little MCM/70 a whopping 100+ KB of effective memory despite having at most 8 KB of physical RAM. “Doing [virtual memory] on a cassette tape seemed like insanity, but it actually worked,” Arpin later remarked, noting that people used AVS to do “pretty serious programming” successfully on the MCM/70. Arpin’s forward-thinking software design allowed the MCM/70 to punch above its weight in running complex APL programs. He continued to be a key figure in later MCM models (even serving as the primary architect of the enhanced MCM/900 system in 1978). Though less publicly known, André Arpin’s contributions were vital in making the MCM/70 a usable personal computer and not just a hardware curiosity.

Together, Kutt and Arpin exemplify the blend of vision and engineering that made the MCM/70 possible. Kutt provided the dream (and the business hustle) of personal computing freedom, while Arpin and the engineering team executed that dream in silicon and code. Their collaboration, along with contributions from others like Laraya, Ramer, Genner, and Smyth, resulted in a machine that was remarkably sophisticated for its time.

Technical Specifications and APL Software Innovations

What made the MCM/70 so unique in 1974 was its technical design – it was a self-contained personal computer with features previously found only on much larger systems. Here are some of the notable specifications and innovations of the MCM/70:

- Microprocessor: It was powered by the Intel 8008 CPU running at 0.8 MHz. The 8008 was Intel’s first 8-bit microprocessor, and the MCM/70 was among the very first commercial products to use it. Later MCM models (such as the MCM/800 and /900) would use advanced bit-slice processors for more speed.

- Memory: The machine came with 2 KB of RAM standard, expandable up to 8 KB. While this seems tiny, the MCM/70 made up for it with 14 KB of ROM containing software, plus its innovative virtual memory. Using the AVS system on cassette, it could automatically swap data to tape and handle programs requiring over 100 KB of memory, an unheard-of capability on a microcomputer then.

- Display: The MCM/70 featured a one-line, 32-character display built into the case. This display was a Burroughs Self-Scan plasma panel, which glowed orange and was similar to those used in high-end calculators of the era. While only one line, it was alphanumeric and interactive – users could see their typed commands and the computer’s responses scroll by, one line at a time. An external monitor was not initially supported on the MCM/70, though later models (MCM/800 and beyond) added the ability to use a CRT screen.

- Keyboard: A full APL keyboard was integrated, with 46 keys using the IBM 2741 APL typeball layout【36†look 188 401】. This meant the keys were labelled with special APL symbols (⊢, ⊣, ↑, ↓, etc.) as well as standard letters, allowing users to program in APL directly. The keyboard also had a START key and control keys. This custom keyboard was essential because APL’s character set went far beyond a normal QWERTY keyboard.

- Storage: Dual cassette tape drives were built into the front panel (one drive on the base model, two as an option). These digital tape drives served a dual purpose: they provided removable storage for saving programs and data, and they acted as virtual memory extensions via the AVS system. Each tape could hold roughly 120–150 KB of data. The system’s EASY operating system managed file operations on tape (storing, retrieving, deleting data), while AVS managed the swapping of memory contents to tape behind the scenes to enlarge the workspace. This arrangement let the MCM/70 run much larger APL programs than would otherwise fit in 8 KB of RAM. It was also effectively an early “save state” feature – if power was lost, the MCM/70 could save the memory to tape and later restore the session.

- Power and Battery Backup: Impressively, the MCM/70 included a built-in power failure protection system (designed by engineer Ted Edwards). If the power went out, a backup battery would automatically keep the machine running long enough to preserve the session. For short outages, the computer could continue on battery; for longer outages, the system initiated an orderly shutdown, automatically dumping the contents of RAM to cassette tape before powering down. When power returned and the batteries recharged, the MCM/70 would resume where it left off, restoring the RAM content from tape. This kind of suspend/resume capability was highly advanced for 1974 – something most personal computers wouldn’t offer for decades.

- Size and Weight: The MCM/70 was designed to be luggable. Its bare chassis measured about 13 inches wide by 15.75 inches deep and 5.25 inches high, and it weighed around 20 pounds (9 kg)【36†look 188 401. It wasn’t exactly lightweight, but it was portable compared to minicomputers of the day. MCM even offered an optional carrying case so that the unit could fit under an airline seat, emphasizing that you could travel with your personal computer – a radical idea at the time.

- Operating System and Software: The system ROM (14 KB) contained not only the APL interpreter (dubbed MCM/APL), but also the EASY tape operating system and the AVS virtual memory manager. In essence, the MCM/70 had a built-in OS optimized for APL. The choice of APL as the primary (and initially only) user language set the MCM/70 apart. It was the first commercially available computer to make APL its sole user language, allowing users to write programs for math, engineering, and business with powerful one-line array processing commands. The included MCM/APL was largely compatible with IBM’s APL\360 (so programs could be shared from mainframes), but it was tailored to run in a tiny memory footprint – a significant technical accomplishment by Ramer, Arpin, and Genner. The MCM/70’s introductory manual proudly stated that “the simplicity of the MCM/70 and its associated computer language (known as APL) make personal computer use and ownership a reality… Enjoy the privilege of having your own personal computer – it’s a privilege no computer user has ever had before the MCM/70… Good luck, and welcome to the computer age!”. This captures how novel it was to have a personal machine running a high-level language out of the box in 1973.

In summary, the MCM/70’s technical design was truly ahead of its time. It delivered an all-in-one personal computing experience with features like an integrated screen, storage, high-level language, and even virtual memory – things that early “homebrew” computers like the Altair or IMSAI did not offer without significant expansion. The MCM/70 was not just a bare-bones microcomputer; it was a complete system aimed at real productivity tasks. This is why historians like Zbigniew Stachniak argue it was “the first truly usable microcomputer system” – a machine that an individual could actually use for practical computing, not merely a hobbyist’s assemble-it-yourself gadget.

Ahead of Its Time: Comparison with Contemporaries

To appreciate the MCM/70’s place in history, it’s useful to compare it to other early personal computers of the 1970s and highlight what made it unique:

- Versus the Altair 8800 (1975): The MITS Altair, often celebrated as the spark of the home computer revolution, was introduced in January 1975 as a $397 kit. The Altair was essentially a box of circuit boards that blinked lights; it had no keyboard, no display, and only 256 bytes of memory in its base configuration. Users had to toggle in machine code or attach teletype terminals to program it. In contrast, the MCM/70 two years earlier came fully assembled with a keyboard, display, storage, and a high-level APL environment ready to go. It could be argued that the MCM/70 was closer in spirit to what we think of as a “personal computer” than the Altair was, despite the Altair’s fame. That said, the Altair’s low price and openness to tinkering made it popular among hobbyists – an audience MCM did not target.

- Versus the IBM 5100 (1975): IBM’s first “portable” computer, the 5100, debuted in 1975 and actually had similarities to the MCM/70. The IBM 5100 was a luggable 50-pound machine with a built-in monitor, tape drive, and the ability to run APL (and BASIC) – but at a astronomical price (~$10,000) and intended for professional use. In essence, IBM validated MCM’s idea that there was demand for a small self-contained computer capable of running powerful languages. However, IBM’s marketing might and existing customer base meant the 5100 garnered more attention in business circles. The MCM/70, despite beating IBM to market with a portable APL machine, couldn’t compete with Big Blue’s resources. IBM was also one of MCM’s first big competitors – as early as 1974, IBM obtained a couple of MCM/70 units for “research”, and by 1975 IBM was preparing their own offering. Ultimately, when IBM and later Apple entered the personal computer arena, they overshadowed smaller players like MCM.

- Versus the Micral and other early micros: The French Micral (R2E) is credited by some as the first commercial microcomputer (announced Feb 1973). However, the Micral was designed for process control and didn’t target personal interactive use – it lacked a keyboard or display initially and required programming in machine code. The MCM/70, conversely, was explicitly aimed at personal computing, providing an interactive language and self-service operation. Other early micros like the SCELBI-8H (1974) or Mark-8 were kit computers for hobbyists and were even more primitive (simple LED displays, no built-in high-level language). In short, MCM/70 stood out by being a turnkey personal system, not a DIY project or a specialized controller.

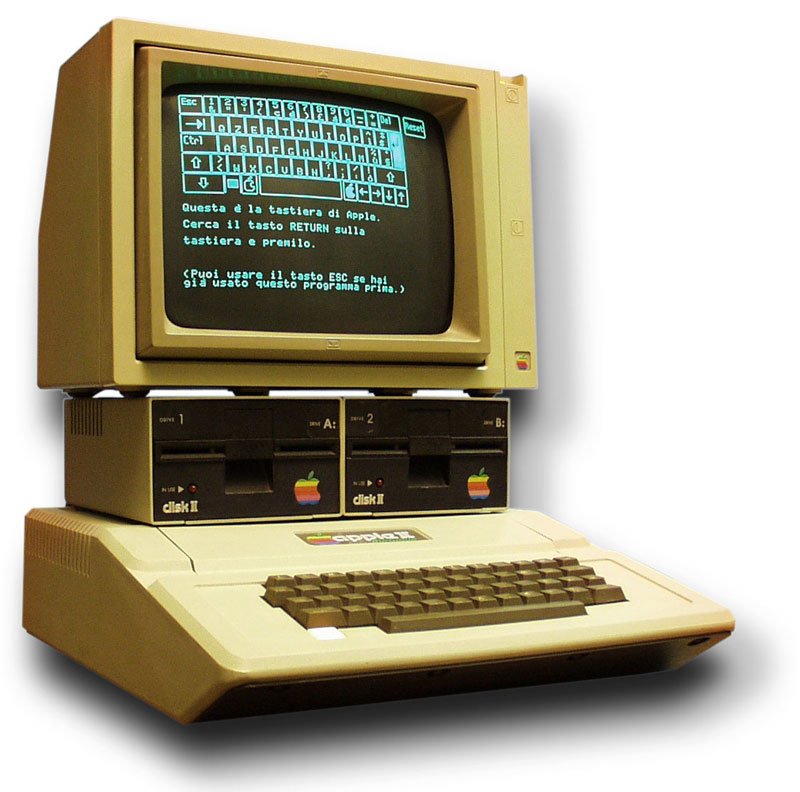

- Versus the Apple I and II: The Apple I (1976) was a bare circuit board that required the user to provide their own case, power supply, keyboard, and display. Only a few hundred Apple I’s were ever made. The Apple II (1977) was a polished product with color graphics and expandability that ultimately captured the imagination of the public. By the late 1970s, the Apple II’s lower cost (around $1,300) and capabilities (especially with the VisiCalc spreadsheet in 1979) made it a huge success. Compared to Apple’s offerings, the MCM/70 was far more expensive and text-bound (APL on a one-line display, no graphics). As personal computing shifted toward a mass market, the Apple II’s affordability and software (games, spreadsheets, BASIC programming) drew customers away from high-priced niche machines like MCM/70. It’s telling that many people bought the Apple II specifically to run VisiCalc, something MCM/70 couldn’t compete with once that killer app arrived.

In summary, the MCM/70’s uniqueness was in being an integrated, user-friendly microcomputer very early on. It was not a kit or a hobby board; it was a functional personal computer concept when the world had barely conceived of such a thing. It pioneered features (portable design, built-in high-level language, virtual memory) that some competitors wouldn’t implement until years later. However, these very strengths (self-contained design, APL focus, high quality) came with a trade-off: cost.

The MCM/70 was expensive for the mid-1970s, which limited its reach, especially once cheaper machines appeared. In a sense, MCM/70 and its European counterpart Micral were “there first” in the microcomputing arena but ended up confined to a small early-adopter market. They proved the concept, but they “paid the price for being there first” when bigger players and broader trends took over.

Launch, Reception, and Market Challenges

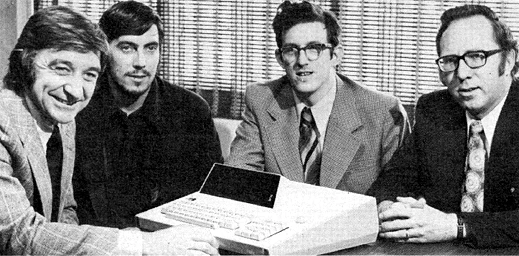

The MCM/70 made its public debut in fall 1973 to significant interest. MCM held a press conference on September 25, 1973 in Toronto to announce the machine, followed by unveilings in New York and Boston in the days after. At the Royal York Hotel event in Toronto, Mers Kutt and his colleagues (Gordon Ramer, Ted Edwards, Reg Rea) stood proudly around a small beige machine about the size of an electric typewriter. Observers noted its built-in keyboard, glowing one-line display, and its resemblance to an oversized.

But as Kutt demonstrated, “this was much more than a simple adding machine”spacing.ca – it was a fully programmable personal computer. The notion was so novel that the company felt it had to stress ease-of-use: MCM touted that the MCM/70 was “of a size, price and ease-of-use as to bring personal computer ownership to business, education and scientific users previously unserved by the computer industry.” In other words, they were carving out a new market between simple electronic calculators and complex mainframes.

Early reception in the tech community was quite positive. As mentioned, in 1973, tech media lauded Canada’s lead in this new field of personal computing. Computer magazines and journals noted features like APL availability and virtual memory that were previously unheard of in small machines. The MCM/70 garnered international attention at launch, even as far as Europe – one prototype had been shown in Paris in September 1973 (coinciding with R2E’s Micral exhibit).

Potential customers in academia were excited: by 1976, an estimated 27.5% of MCM systems sold in North America went to educational institutions, where having a personal APL machine for students or professors was very attractive. At Yale University, for example, computer science professor Martin Schultz remarked in late 1973 that the potential for a system like the MCM/70 at Yale was “very high”. Clearly, MCM struck a chord with those who understood its capabilities.

However, turning a pioneering concept into a sustainable business proved challenging for MCM. One major hurdle was pricing. The MCM/70 was a high-end product and priced accordingly. In 1974, a base model with minimal memory and no extras cost around $3,950, while a fully expanded system could run up to about $9,800. (These are equivalent to roughly $20,000–$50,000 in today’s dollars.) As the company introduced upgrades, prices remained steep – the later MCM/800 model in 1976 cost more than $10,000 (the very first unit costing around $20,000)spacing.ca. Such prices meant that individual hobbyists or home users were not the target audience; sales had to come from institutions, corporations, or government agencies with budgets for specialized equipment.

Indeed, MCM/70’s early customer base consisted of forward-thinking organizations that could justify the expense. Notable buyers and users included:

- Government and Military: The Canadian Department of National Defence purchased MCM/800 systems for war-game simulations. The U.S. Army was also an early user of MCM machines.

- Energy and Industry: Ontario Hydro used an MCM/800 at the Pickering nuclear power plantspacing.ca. Chevron’s Oil Research division and Firestone Tire were among the private companies that installed MCM/70s for technical computing tasks.

- Research and Education: Universities like the University of Toronto acquired unitsspacing.ca. NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center had MCM systems, likely for scientific computing with APL. Other MCMs went to hospitals and insurance companies seeking to leverage computing power without investing in a full mainframe.

MCM’s marketing efforts tried to cultivate these kinds of clients globally. The company set up distributor networks in the U.S. and even in Europe (e.g. Sysmo S.A. in France). But building an international sales and support structure was expensive and stretched MCM’s small finances. Every sale was a challenge, as one team member recalled, because they were selling something “totally new” that people had never seen before. Convincing businesses to trust a tiny Canadian startup’s computer required significant hand-holding, training, and demonstration of what APL and virtual memory could do. This was especially true at a time when even the concept of a “personal computer” was unfamiliar – MCM had to educate the market from scratch.

The company also faced technical hiccups that affected its momentum. An infamous issue occurred with the power supply design: early units given to potential distributors had problems where a power failure was supposed to trigger the backup battery, but instead some prototypes literally smoked or blew fusesspacing.ca. This bug forced MCM to halt shipments and fix the design, causing a serious financial crisis just when they needed to be impressing investors and clientsspacing.ca. By the time the problem was resolved, unfortunately, Mers Kutt and some other key employees had left the company (around 1975)spacing.ca. The loss of its founding visionary at such a critical juncture was a blow to MCM.

On top of that, mainstream exposure was limited. MCM lacked the funds for splashy advertising or major trade show appearances. Notably, they never exhibited at the annual NCC (National Computer Conference) in the U.S. during the 1970s, missing opportunities to get on the radar of the broader industry. By contrast, competitors and newcomers were starting to make waves: in 1977, for instance, Radio Shack and Commodore would launch affordable home computers, and Apple’s machines began gaining media attention.

In summary, while the MCM/70 was greeted as an innovative marvel in 1973-74 and did secure some prominent customers, market realities (high price, a niche language, a tiny company behind it, and a nascent demand) kept it a relatively low-volume product. MCM did manage to sell on the order of a few hundred units in its entire lifespan – enough to keep going for a while, but not enough to break into the mainstream. The next section explores how these challenges culminated in the eventual decline of MCM and why the MCM/70 didn’t achieve the lasting fame of some peers.

Limitations and the Decline of MCM/70

Despite its technological head start, the MCM/70 and its successors ultimately succumbed to a variety of limitations and challenges. Several factors contributed to the decline of MCM as a company and to the MCM/70’s status as a forgotten footnote rather than a household name:

- High Cost and Small Market: The MCM/70’s steep price (several thousands of dollars) put it out of reach for hobbyists and the general public. It was essentially a premium product looking for a market. Only niche professional users could justify it, which severely limited the sales volume. As the 1970s progressed, the market for personal computers shifted to a lower price point – thanks to mass-produced chips and the economies of scale achieved by companies like Commodore, Tandy, and Apple. MCM, a small operation, couldn’t compete on cost, and it never achieved the sales volume to significantly bring prices down.

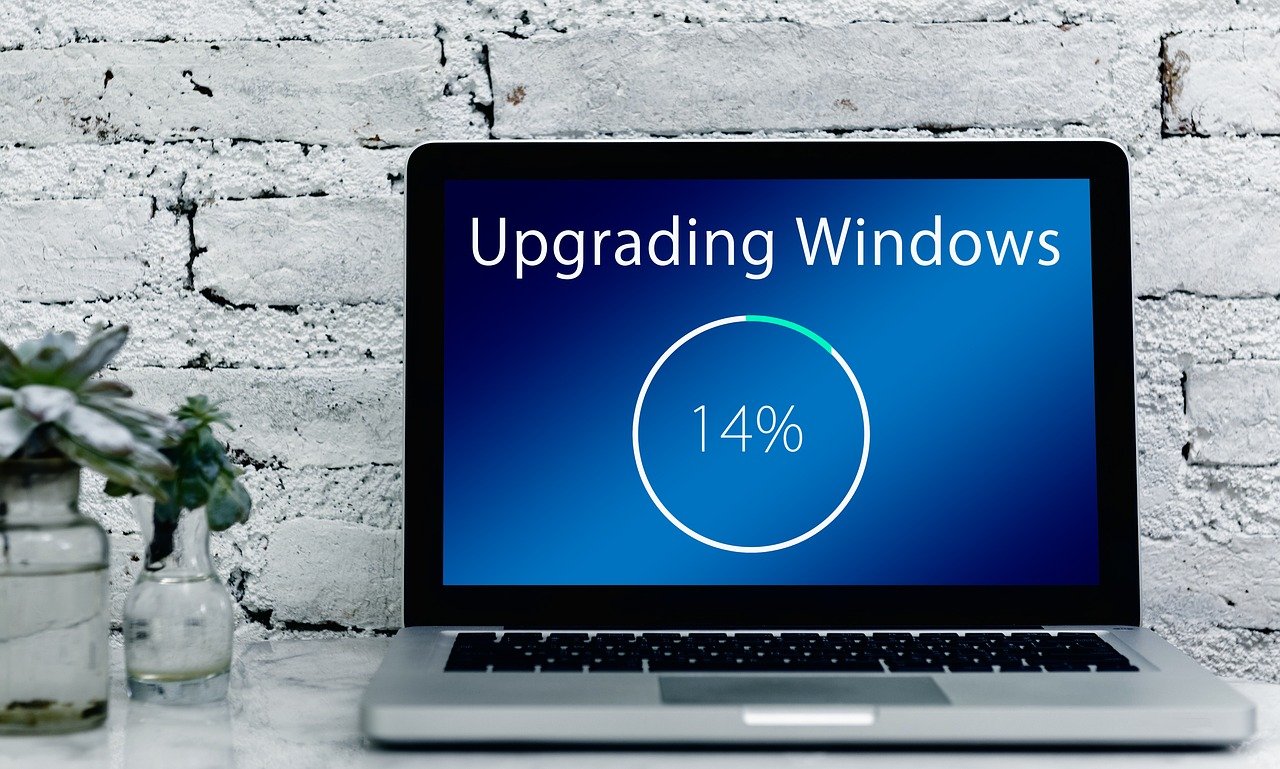

- Niche Language (APL) and Software Gaps: While APL was a powerful language, it was also esoteric and not widely known outside certain scientific and academic circles. MCM’s insistence on APL as the primary interface was a double-edged sword. On one hand, it made the MCM/70 immensely capable for math and logic problems; on the other, it alienated the growing community of microcomputer enthusiasts who were rallying around simpler languages like BASIC. By the late 1970s, the tide in personal computing had turned strongly toward BASIC (and later Microsoft’s MS-DOS) for general usespacing.ca. As Birnam Woods, MCM’s last CEO, later admitted, “We were against the tide… The tide for APL… was on its way out… At that point in time the operating system of the day was Microsoft [DOS].”spacing.ca. MCM recognized this a bit too late – there were internal discussions about adding a BASIC interpreter or word processor to broaden the MCM machines’ appeal, but these plans never materialized in time. The company’s staunch focus on APL meant that when killer apps like VisiCalc (the first spreadsheet, on Apple II) came along, MCM’s platform couldn’t participate.

- Limited Display and Graphics: The one-line display, while sufficient for APL programming, was a limitation as computing use-cases expanded. By the late ‘70s, competing micros offered full-screen text and even rudimentary graphics (e.g. Apple II’s color graphics, Commodore PET’s 25-line display). The MCM/70’s later models did introduce optional CRT displays and larger screens (the MCM/800 could drive a monitor, the MCM/900 had a built-in CRT). However, those enhancements came as the company was already on the back foot. The original MCM/70’s minimal interface may have caused some prospective customers to perceive it as underpowered compared to flashy new PCs with screens and sound.

- Performance Constraints: The MCM/70’s use of the 8008 microprocessor and limited memory made it relatively slow for certain tasks. Users doing intensive computations in APL could find it leisurely in performance. One contemporary recollection noted that having a personal APL machine was great, but the MCM/70’s “leisurely performance” (especially the later MCM/700 running the same CPU) left some users dissatisfied. In essence, MCM/70 provided mainframe-like capabilities, but at a fraction of the speed – acceptable in 1974 for light workloads, but increasingly frustrating as expectations rose. By 1977-78, newer 8-bit CPUs (8080, Z80, 6502) and better memory meant other personal computers were catching up or surpassing the MCM in performance at lower cost.

- Competition and Marketing Failures: As the personal computer market blossomed, competition exploded. MCM faced well-funded entrants like IBM, HP, Xerox in the high end, and a swarm of home computer makers in the low endspacing.ca. IBM in particular, with the 1975 IBM 5100 and later the 1981 IBM PC, became a dominant force that MCM couldn’t match in credibility for business buyers. Meanwhile, MCM never had strong marketing channels to consumers or hobbyists. They didn’t build a community or software ecosystem around their machines beyond APL enthusiasts. By the late 1970s, a personal computer without a community or third-party software was a tough sell. MCM’s attempt to expand via a French subsidiary (Sysmo in Paris) also faltered – Sysmo sold some MCM machines for business applications, but programming in APL (a scientific language) was a mismatch for typical office needs, and Sysmo went bankrupt in 1978. In North America, MCM’s advertising was minimal and they failed to generate buzz at key industry events. In short, they had an incredible product but not the marketing muscle or strategic partnerships to popularize it.

- Internal Turmoil and Funding Woes: MCM was chronically undercapitalized. The initial success and hype did not translate into the sustained investor support needed to scale up production and marketing. When technical issues (like the power supply flaw) occurred, the lack of a financial cushion nearly sank the firmspacing.ca. Founder Mers Kutt’s departure by 1975 created a leadership void; while others carried the torch, one senses that the original passion and direction suffered. Later, MCM did bring in new management and continued to innovate technically (the MCM/1000 “Power” project in 1980 aimed to modernize the design, and a next-generation design called A*2 was being developed). But the company could not secure the rapid funding and development needed to keep pace with the PC boom. By 1982–83, MCM ran out of money and was forced into receivership. The remaining technology was sold off (rights to the unfinished A*2 were sold to Ampex, which also eventually shelved it).

All these factors culminated in the end of MCM as a computer manufacturer. In 1982, less than a decade after the triumphant launch of the MCM/70, the company foldedspacing.ca. They had reportedly sold only a few hundred machines in total – not insignificant for a pioneer, but not enough to make a dent in the burgeoning PC industry.

As one analysis put it, MCM and its French counterpart R2E “both fell prey to their own limited market space, paying the price for ‘being there first’ but unable to break the barrier of… aloofness” in a rapidly growing consumer-driven market. The MCM/70 was technologically successful but commercially ahead of its time to a fault, arriving before the world was ready, and then fading as the wave finally caught up.

Legacy and Rediscovery of a Pioneer

Although the MCM/70 slipped into obscurity after its demise, its legacy as a pioneering personal computer has been reassessed in recent years. Computer historians now recognize the MCM/70 as a milestone in the evolution of personal computing – particularly for demonstrating that a microprocessor-based machine could directly serve end-users with high-level computing tasks. In hindsight, many of the MCM/70’s features and ideas were harbingers of the future:

- It proved the concept of an all-in-one personal microcomputer – combining processing, storage, display, and input in a single compact unit. This was a model later seen in the Commodore PET, Osborne 1, and eventually modern laptops, but MCM did it in 1973.

- It introduced features like virtual memory, power-fail recovery, and integrated high-level language at the micro scale, well before such capabilities became common in personal computers. These are now taken for granted (e.g., every modern PC uses virtual memory and has battery backup in laptops), showing MCM was forward-thinking.

- It helped pioneer APL on personal machines, and more broadly, the idea that personal computers could tackle serious computational problems (not just play games or balance checkbooks). In a sense, MCM/70 was an early ancestor of today’s high-level computing environments on desktop computers.

- Its fate also taught a lesson: being first isn’t enough. The industry often cites MCM/70 (and others like it) as examples of the “right idea at the wrong time”. As historian Zbigniew Stachniak noted, the MCM/70’s story shows that by the early 1970s, “affordable personal computing was at our fingertips” – the technology was ready, even if the market wasn’t fully prepared to embrace it without the hobbyist catalyst that came later.

For a long time, the MCM/70 remained largely forgotten, especially outside of Canada. But there has been a renewed interest among computer history enthusiasts in uncovering its story. In 2003 (on the 30th anniversary of the MCM/70), York University in Toronto hosted reunions and exhibits, gathering Mers Kutt and other members of the original MCM team to reflect on their work. Professor Zbigniew Stachniak of York University spent years researching the machine and in 2011 published a comprehensive book titled Inventing the PC: The MCM/70 Story.

This book and Stachniak’s related articles have been instrumental in documenting the MCM/70’s development and significance. The York University Computer Museum now holds a collection of MCM artifacts, papers, and even working units of the MCM/70 and its later models. An online exhibit by the museum also showcases photos, drawings, and details of the MCM/70 for the publicspacing.ca.

This historical attention has helped place the MCM/70 back on the map as an early PC pioneer. Media articles have highlighted it as “the first personal computer you never heard of” and pointed out that Toronto briefly “invented the PC, then forgot about it”.

There is a certain patriotic pride in Canada for the MCM/70, as it represents a time when a Canadian company was on the cutting edge of a field later dominated by Silicon Valley. Mers Kutt, now in his 80s, has received some late recognition – he was dubbed “Canadian hailed as father of the PC” in a 2003 Globe and Mail piece, and he’s given interviews reflecting on the MCM/70’s creation and the ups and downs that followed.

Ultimately, the MCM/70’s legacy lies in its role as a trailblazer. It foreshadowed the personal computing revolution by demonstrating many key elements of what a personal computer could and should be. It influenced (directly or indirectly) later designs – for instance, it’s intriguing to consider that IBM had two MCM/70s in-house for study in 1974, possibly informing projects like IBM’s SCAMP prototype and eventually the IBM 5100. Even if MCM/70 didn’t achieve commercial success, it showed the way.

As noted in a retrospective, “it is difficult to explain unequivocally why the MCM/70 was not the commercial breakthrough to launch the personal computing industry” – timing and market conditions had much to do with it. But its existence proved that, “with the advent of microprocessor technology, affordable personal computing was at our fingertips”, and it wasn’t too farfetched to imagine (as Mers Kutt did) millions of small computers changing the world.

In conclusion, the MCM/70 microcomputer truly was “the forgotten pioneer of personal computing.” It was ahead of its time both technologically and conceptually. While it didn’t ignite the PC revolution – that honor went to later, more commercially savvy entrants – it remains a remarkable achievement. Today, thanks to historians and dedicated museums, the MCM/70’s story is being remembered and told to new generations. It stands as a testament to the ingenuity of its creators and a reminder that some pioneers, even if overshadowed, played a crucial role in shaping the personal computing landscape we know today.

The next time we marvel at our lightweight laptops or powerful desktops, we might tip our hat to that 1973 beige box from Toronto that quietly pointed the way to the computer age for everyone. The MCM/70’s legacy lives on as an inspiration and an important piece of the puzzle in computing history – a pioneer finally getting its due recognition.